It’s easier than ever to listen to practically the entirety of recorded music. But for musicians, it’s harder than ever to make money. On Episode 31 of The Politics of Everything, hosts Laura Marsh and Alex Pareene talk about the economics of the music industry with the English musician Tom Gray, who founded the #BrokenRecord campaign, and David Turner, who writes the newsletter Penny Fractions. Did streaming save music, or is it killing it? Should we blame Spotify or the record labels for the industry’s problems? And what should be done to make the music business more equitable? Tom Gray: It took me five years to find a copy of Starsailor by Tim Buckley in the 1990s. Five years. And when I got it, I was not happy. I did not like that record. That was five years of shuffling through boxes. I mean, streaming is incredible. Streaming is all the music in the world in your back pocket. Who wouldn’t want that? Laura Marsh: That’s Tom Gray. He’s a musician we’ll be hearing from later. He’s talking about this moment in the mid-2000s that changed music. Suddenly, you could listen to almost any song, any piece of music, whenever you wanted it on your computer or on your phone. Alex Pareene: You didn’t have to pirate it through services like Napster or Limewire. You didn’t have to pay per track the way you did on iTunes, either.Laura: There were all these streaming services. Spotify is obviously the big one; it was founded in 2006, and finally launched in the Unites States in 2011. Alex: There was also Grooveshark. There was YouTube. There was Pandora. Laura: I remember some of those. And the result has been that there’s more music available now to the general public maybe than ever. But, a decade on, musicians are struggling to make ends meet, and a global pandemic has made that even harder. Alex: Today on the show, we’re talking about the music industry, some of the biggest entertainment companies in the world, and a tech giant. Laura: We want to talk about how streaming is changing music. Alex: Or maybe the question is: Can music survive streaming?I’m Alex Pareene. I’m a staff writer at The New Republic.Laura: And I’m Laura Marsh, the magazine’s literary editor. Alex: This is The Politics of Everything.Laura: So today we’re talking to Tom Gray. He’s a composer, songwriter, and founder of the #BrokenRecord campaign. Tom, we’re talking about music in the age of streaming. Can you give us a sense of what it’s like to be a working musician nowadays, especially over the last year? Tom: It’s quite hard. There are 50,000 musicians in the United Kingdom, and the median income is somewhere around 20,000 pounds a year. Alex: For our American listeners, that’s around $28,000.Tom: The truth is, as I’ve progressed through this industry, I’ve seen more and more of my fellow musicians coming from more privileged backgrounds, because it is, I think, harder and harder to have a sustainable career in the arts without coming from privilege. So when everything started closing down, it was like “Oh God, the licensing money is going to disappear.” I could see touring income was obviously going to disappear. And with all that, merchandise and all the rest of the incomes that come ancillary to touring. And we’re left with streaming, we’re left with recorded music. Streaming now accounts for about 85 or 90 percent of recorded music sales. And it pays extraordinarily badly. Laura: Let’s talk about that. What is the general deal? I’m sure that this varies artist by artist. But if you are a musician and your music is on Spotify, what are you expecting to get from that? How does streaming actually pay musicians? Tom: So you have to understand something called the revenue share model, which is a lot of how all streaming services work, actually, and music is no different. They collect all the money from everyone’s subscriptions, pull all the money from advertising, and then they divide that by the total number of streams in the system. That’s the only way you achieve any kind of per-stream rate. There is no such thing as a per-stream rate. Laura: It’s not the same as back in the old days, when if you went and bought a single, a single was, say, five pounds, $5, and everyone who bought it paid the same amount. But in this case, you’re competing with every other person who has ever made music to get a share of one pot.Tom: And of course what will happen is—as you’re aware—some people have family plans, or duo plans, or they have all these other bundled plans, or they’re listening on “freemium,” and their streams will have different valuations based on how much money they’re putting into the system. In a family plan, that’s six accounts for like 15 bucks or 20 bucks or whatever. Take the 15 pounds in the UK and divide it by six. That’s how much per individual is paying for their total streams. Now, if each of those people is listening to an average amount of music, which is say 500 or 800 tracks a month, their streams are worth an awfully lot less than people who are listening on a premium. You understand how it starts to break down, too. I saw an audit of a pretty big artist recently. In one quarter, they were paid 36 different stream rates by one platform.Alex: You can’t say Spotify pays artists X cents per stream or something because it varies so much by who streamed it, how much they stream, and how much they are worth to Spotify.Tom: Exactly. And when we talk about per stream rates, what we’re doing is sort of smushing all of this data together and dividing it up and looking at averages and trying to work out basically where they are. When you do that with Spotify, you come out with a horrendously low rate: around $0.003 per stream, which is about a third of what Amazon is paying. And that’s because they have premium services and all of this bundling and these marketing schemes—they give away Spotify with phones and things like that. So people are listening for free, essentially.Laura: Twenty, 25 years ago, if you were someone who really loved music, how much do you think you were spending per month buying records? Tom: This is interesting. I actually looked into this data. It turns out that the amount of money that people spend on music has basically not changed. Laura: That surprises me. Because I would think if you’re a music lover and you’re buying maybe three or four albums a month, that’s like maybe $50, $60, $70, compared to like $15 a month for a premium account on Spotify. Tom: We’ve got to remember that the big music listeners and the “not really very interested but quite like music on in the background” people have been totally cannibalized together by streaming. Your big fan puts only 10 bucks into the system and the person who doesn’t care anything about you only puts 10 bucks into the system. So what’s actually happening is there are more listeners, there are more people paying for music. But when you do the average, it comes out basically the same, because there used to be people who would spend 300 bucks a month on music, but they don’t do that anymore because they’re streaming. So the average per individual per consumer has basically not changed. Alex: That’s interesting. I often think about this in the context of how to pay for journalism, which obviously is important to Laura and me. But when people say people aren’t willing to pay for the news, I always think: Why are people paying an internet service provider to get on the internet? They’re paying to get their news and they’re paying to stream their music. And when, 25 years ago, you would have just bought a newspaper, bought a record, there wasn’t an intermediary in there that you had to pay for access to those things. You just went to the store and you got those things. Tom: When people really start thinking about streaming, the thing that upsets them most is when they realize that their subscription doesn’t go to the music that they listen to. It just goes off into this big pot that gets shared out amongst everything else. The average listener, if you are listening to 500 or 800 tracks a month, probably only about two bucks of your 10 bucks is going to the music that you listen to. The rest is going to music that you don’t listen to. I don’t want to give my money to music that I don’t like. I don’t want to fund music that I hate. In fact, quite the opposite! Where is the moral right of the consumer in this? I mean, when you pay your 10 bucks, you’re funding misogynistic hip hop, you might be funding some of the worst jazz in the world. This is where your money is going. So that, for me, is a curious problem. It’s a much bigger question for culture widely, I think, because if we’re saying everyone’s just chucking in money to fund the mainstream, which is what’s happening—all the money is going to the most mainstream thing—curiously, what we’re doing is we’re all funding the mainstreamization of culture. We’re all going, “Yes, please. Let’s all fund that algorithm that makes us all listen to the same 10 songs.”Laura: I’m curious for your thoughts about how streaming has changed tastes. Before streaming, people who didn’t want to listen to chart music or mainstream music could go and seek out their favorite bands’ records, and would often spend a lot of time searching for rare releases and stuff like that. And that whole culture has really been destroyed by streaming. In the early days of Spotify, I remember getting it and being like, “This is amazing, because I can find tracks that I would have had to travel to a different country to buy in a record store in, like, Nebraska, and now I can access it.” So for a while, it kind of seemed like it was opening up tastes. We seem to have moved past that into this kind of sludge. If you look at the most-streamed songs it’s like 10 songs by Ed Sheeran and Drake, and you don’t see a lot of diversity in what breaks through. Tom: You’re absolutely right. It’s wrong to not say that streaming is this incredible technology for music discovery, because it is. It’s unbelievable. The problem we’ve got is that streaming solved distribution for the record companies, but it did a total disservice to the artistry of music-making. You’ve got Daniel Ek telling us now that we all should just be putting out more and more music all the time, all day long.Laura: Daniel Ek is the CEO of Spotify, is that right? Tom: Yeah, he’s that guy. And he’s like, you should just make more music all the time. That’s the only way to feed the algorithm. You know how kids say you have to trick the meta on Instagram or on Tik Tok to get on top of the algorithm, you have to do three posts a day and you have to use these hashtags? He’s saying that’s what we need to do with music. We need to keep making more and more of this crap, just throwing it into the system so that we listen to more. And of course, the problem with music is that if you’re making loads of it, it’s shit. Laura: You have been doing some work on this and organizing. What’s the backbone of your campaign? Tom: Look, we’ve all been saying to the industry for years we need to sort this out. We complain about it all the time and they do nothing about it. And so I thought, well, I know the only thing that they’re afraid of, and it’s not me: It’s legislation. Laura: Obviously we’re based in the U.S. and your work is based in the U.K., so there’ll be some differences. But what kind of regulation are you trying to encourage the U.K. government to adopt? Tom: Three things. There’s a right, which is actually a performance right, called equitable remuneration, which gets paid by radio in the U.K. and gets paid by satellite radio in the United States. That’s a right that’s associated with radio performance. And because I think so much of streaming is playlisting now, and is this noninteractive system where you just press play and it’s on all day long—how is that different from Pandora? If Spotify calls it radio—it says Beatles radio—I’m like, well, some percentage of this money in the system should be paid directly to performers via this right called equitable remuneration. And that scares the hell out of record companies. Because the big problem in all of this is not the streaming services. I mean, the streaming services are shitty horrible people, right? They’re like Silicon Valley, “Who cares, we’ll set the world on fire and leave it burning in our wake, we don’t care, we just want to get rich and own a lot of stuff.” And that’s fine, but the people who were making most of the money from streaming—all the major rights-holders, which is Sony, Universal, and Warner—I think nine or 10 billion from the total of 12 billion that came from streaming went to those three companies. And globally, they have about 70 percent of the market, but that’s because they don’t have China and India and places like that. It may be as much as 80 or 90 percent of the market is owned by three companies in the United Kingdom. Now the contracts that these companies do are called standard record deals. And essentially this is how it works: They give an artist some money to make a record and to buy them out of their rights. Then the artist pays them back for that money from their small royalty, their percentage—from their tiny percentage. What you’d hope for, what you’d wish for, is a system where they give you some money, and then when they’ve made that money back, they start paying you a royalty. But that’s not what happens. You pay them back from your tiny percentage. So most artists never leave debt. They never leave debt. I mean, we know from Universal’s testimony in a recent parliamentary inquiry, they were saying, essentially, that of their total revenues, only about 20 percent of it they spend on what they call A&R, which is all of their advance payments. All of that music production, everything. So we could work out that basically only about 5 percent or lower of Universal, the world’s biggest record company, only about 5 percent is being paid to artists as royalties.Laura: So they’re taking a big slice of the pie or, in fact, leaving just a very small slice of the pie for other people. How does the equitable remuneration cut them out if you’re being paid as if you’re on the radio? Do they get less money? Does it go straight to the performer? Tom: By precedent, in the U.K., outdoor remuneration is paid 50 percent to the rights-holder, to the record company, and 50 percent directly to the performers, irrespective of contracts, irrespective of debt, irrespective of anything. So it’s just money straight out from stream one to the performer. That’s why I want it: Because it’s just money in the pockets of musicians. If I have to take it off Universal, so be it. That’s who it’s coming off of. The platforms are getting 30 percent. The record companies are getting about 52 or 55 percent. What are the costs now for record companies? What costs have they got? They’re not manufacturing anymore. They’re not distributing anymore. They haven’t got trucks driving CDs all over the country anymore. They’re not paying A&R scouts in every city and town to go and stand in bars and listen to music. They’re just looking at Tik Tok. I mean, what do they do any more for 95 percent of the money? They’re just marketing companies that are pocketing 95 percent of the income. We need to massively reset everything in this because it’s a horror show. These companies should have done away with their old contracts from the twentieth century as soon as all of this came along. They haven’t. They’ve done nothing. So I’m sort of swinging a hammer at it using the law. Laura: You said there were three things that you want. That was one of them. What are the other two? Tom: I’m trying to get the Competition and Mergers Authority in the United Kingdom to investigate them all. Laura: Record companies as potentially monopolies?Tom: Yeah, as an oligopoly. Universal is part-owned by a Chinese company called Tencent, who part-own Spotify, and Spotify part-owns Universal and Tencent. I mean, call me old-fashioned. There’s stuff going on there that isn’t great. Laura: What’s the third thing that you were pushing for?Tom: The third thing that I’m asking for is the creation of an actual regulator for the music industry. Essentially, music is being treated as a loss leader across the board, by all these companies. Spotify wouldn’t care if they were selling carpets or trousers—sorry, pants. It’d be the same thing, right? They’d just be selling it cheap and growing their company as fast as they possibly could. Spotify doesn’t care about profit. They have never tried to make a profit. They’re trying to grow their user base as fast as possible. And to do that, they are loss leading with a product, and that product is music. And by loss leading with all of the music that’s ever been made, they are loss leading the entirety of musical culture. It’s not good. The example I always use, although I don’t like comparing music and milk, but it’s the one that works best because dairy farmers in the U.K. have a regulator called the Groceries Code Adjudicator, because the big supermarkets use milk as a loss leader. Laura: They sell milk very cheap so that people will say, “Oh, I need a pint of milk and it’s cheap there,” and then they get their other groceries at the same store? Tom: Exactly. That was putting dairy farms out of business. So now dairy farmers have an adjudicator who protects the price of milk. I’m asking for the same thing, but I’m also asking for a more broad-range adjudicator, because there are all kinds of really awful, icky things that are still going on in the music business: I mean, young women being horrifically, exploited and abused, people basically just calling themselves music managers and literally getting off a bus and going, “Hey, I’m a music manager. Have you met me?” and just doing what they like from there on in. And, unfortunately, young kids come along and believe them and find themselves in pretty dark situations. This is the whole problem with music in so many ways, the way that it brings in young people and people of color and just exploits the hell out of them and then leaves them for dead. And I just think that we could do the whole thing a lot better. Alex: I hope so. Tom: Well, one would, wouldn’t one? Laura: So Tom talked with us about the state of the industry today, and how tough it is for musicians. Alex: After the break, we’re asking how we got here. We revisit the early 2000s, when the music industry was facing a crisis and streaming was supposed to save it.Laura: So if you think back to the early 2000s—and it’s kind of a dim memory, this age before streaming—the music industry was already struggling. The thing that people were worried about back then was that no one would pay for music at all in the future, that we’d all just be pirating and downloading illegally for free.Alex: Here’s my memory: I went off to college, and in our dorm, all the dorms were connected on the same network, so everyone was sharing their music libraries. And I was like, “I don’t ever have to buy a record again.” This was in New York. It happened around the same time Tower Records closed here. And it was like, “Oh, I must’ve done that. I and my friends in the NYU dorm must be the people who did that.”Laura: I remember taking my little box of CDs to college with me the first year. And then the second year I was just like, “Oh, I don’t need these anymore. I can play music without having this record collection.”Alex: So you and I, our generation destroyed the industry until these beneficent streaming corporations came in to save it. That’s basically how we understand it happening?Laura: That’s been the narrative that’s formed in my mind over the years. So I can’t understand how things went so badly wrong. I think that’s why we need to talk to another guest. Alex: So we’re joined now by David Turner, who writes the newsletter Penny Fractions, which is about the music streaming business. A small disclaimer, before we get started: David works for SoundCloud, but he wants to be clear that his views are his alone and don’t represent those of his employer. Hi David, thank you for joining us. David Turner: Thanks for having me today. Alex: As a layperson, if you’re interested in the music business, you maybe get the sense that it’s in trouble. You get the sense that artists are not able to make a living through their music anymore, and that everything has been upended by technological change. My question is: Is that accepted story of how the music industry fell apart true? And am I, the music consumer, responsible because in 1999 I downloaded Napster and started downloading Wilco albums? Did I set this all in motion?David: No, you did not set this in motion doing this in 1999. The record industry overall right now is actually doing really, really well—profits are up and have been going upwards since around the mid-2010s. And what has been happening is that artists right now have been raising a lot of concerns about these new digital platforms and these new digital ways of payment. And artists are seeing that these platforms exist and are seemingly making a lot of money off their work, while artists are not seeing that return come in. The big issue with the record industry is the same as it’s always been—it’s the major labels. It’s major labels that have had control dating back to like the 1970s, the 1980s and the 1990s, when we used to have, at one point, six major labels, then five, then four, and now we only have three. So when you start looking at that, it becomes, to me, the much bigger issue, rather than its being an individual platform or individual consumer choice. Alex: I think that’s worth highlighting, because I think people think the music industry is in trouble, but you’re saying the industry is doing fine. The industry is making money under current arrangements. It’s the artists—they’re the ones in trouble.Laura: When I was growing up listening to music, there was this whole scare around people downloading stuff from Napster and teens getting prosecuted for, like, theft of intellectual property. And there was a sense that streaming services were going to save everyone from having to either be criminals or pay an inordinate amount of money to buy a CD. They were seen as this great savior, like iTunes was seen as actually providing a way to monetize music, Spotify was seen as a way of being able to access music and pay for it. What do you make of that narrative?David: I find that narrative on its face laughable. Imagine an industry, a $10 billion-plus industry, that can be taken out by a teenager. That’s hilarious.Laura: So what was piracy? How extensive was it? David: To contextualize piracy a little bit better, internet access wasn’t rampant in the late 1990s—penetration was a little over 10 percent globally. The internet of the late 1990s was not great. You could barely get access to any music. So the idea that all of a sudden the introduction of slow downloads entirely cratered an industry is, to me, specious. And then, to be more serious, there have been a number of academic reports and academic research into this field, and it’s a wash as to whether piracy had a real impact on record industry sales. Alex: Yeah, it’s funny when I’m thinking back. In my memory, I downloaded so much stuff. But then I go back to my favorite records that came out in 1998, 1999, 2000—I bought every single one of them. So in retrospect, I don’t even know what I was spending my family’s precious dial-up internet time downloading.David: There’s sort of that intuitive sense of, I used to buy CDs, and music came on digital, I started downloading music, and that explains everything. But most people continued to buy CDs. Most people still listened to most music on the radio. There are all these other forms that didn’t go away when the internet introduced digital downloads.Alex: I want to get into the economics of this, in the sense that we hear about these incredibly low rates that get paid out to artists per stream. How does the music industry currently make money? Where’s the money coming from, and who’s it going to?David: The way the music industry makes money right now is mostly through streaming. Streaming accounts for, I think, 80, 85 percent of overall recording industry revenue. And most of that revenue can be attributed back to Spotify and Apple. Spotify has a lot of paying subscribers. They have tens of millions—over a hundred million—paying subscribers. And then a lot of it also comes to advertising. Apple also has subscribers, so they make a lot of money from that. And then a lot of it is just subsidized streams—Amazon, YouTube. We don’t really know if those are successful businesses within the Amazon or Alphabet portfolio. We just don’t know that. But the idea is that like 80 percent of that streaming revenue is mostly coming from tech companies. If you notice a trend here, the companies I’m mentioning, among those companies, Spotify is the only independent of those, not owned by a bigger tech company. And it’s also only had two profitable quarters in its more-than-a- decade of existence. So you can see that this isn’t actually a really sustainable or profitable business. But it’s one that is right now being mostly propped up, in Spotify’s case, by investors all across the globe, and finance, advertising, and even the major labels that previously had investment in the company. And then on the Apple/Amazon/ Alphabet side, we really don’t have a great sense. I assume that Tim Cook just sort of looks at the Apple Music costs and just shrugs his shoulders—“Whatever, this is fine.” Alex: Then that money’s going, as you said, primarily to the major labels, right?David: Yes. A majority of that money just goes straight into the major labels. So this is, again, nothing new. This is how things have basically been since around the 1990s, that major labels account for probably over two-thirds of that revenue. And then the rest of that goes through independent labels, mostly represented in the United States by Merlin, which is a big trade group that represents thousands of smaller independent labels. And then outside of those two buckets, there are actual independent self-distributed artists, or labels outside of Merlin. But those represent a tiny percentage of that revenue. It’s very, very small. At this point, a majority of the money being filtered through the major labels or indie labels. Laura: Musicians have been complaining about their relationships with their labels for a very, very long time. Has streaming made it worse? Has it put musicians in an even worse position with relation to their labels? Or is it the same? David: I actually think it’s fairly analogous. I don’t think it’s changed all that much. I mean, the deals certainly have changed. Major labels’ deals have gotten smarter to incorporate more things that artists do. The idea of a 360 deal is that you’re taking some part of touring, merch, and everything that an artist releases. That’s certainly been a newer innovation of the last 20 years. But overall, you can go back to the early twentieth century, when musicians, like blues musicians, were complaining about how record labels treat them. That’s not really any different. A good example is the rapper Silento, who had this song “Watch Me” from five years ago. He signed a five-album deal. He never put out an album. And that’s the kind of deal and classic situation that you would hear from artists certainly 20, 50, even 100 years ago. One interesting wrinkle with streaming—and this is a little bit in the weeds, but it is kind of odd to think about—is that the way that streaming works with artists payouts is that it’s done on a pro rata model. So when Drake puts out a new album, if he puts out a new album and he’s 5 percent of overall streaming that week, he makes 5 percent of the money—he gets 5 percent of the overall pot. So that means that if you put on an album that week that Drake did, you’re going to probably do worse, because all of the streams and revenue is divided out proportionately. So if you put out a new album on a week where there’s a big major release, that’s sucking up all the oxygen. You’re going to actually do worse. Every week, you’re competing against everyone else, because of the way that things are proportionately split out.Alex: Say it’s the 1980s and you’re a college rock band and you sell 10,000 copies of every album that you put out. Ten thousand people are your fans. They buy your record. You’re not penalized for coming out the same week that “Thriller” comes out. But now you would make less money if the indie band had a release the same week as a giant pop star.David: For indie musicians in particular, that is really odd, because traditionally, indie musicians would have no reason to care about the mainstream because they’re in their own economic bubble. Where now you do need to be a little concerned that, hey, Taylor Swift put out a new album. That’s probably when I shouldn’t put out my new album. Alex: I didn’t even realize that part of it.To some extent, I, as a guy in his mid-thirties, am nostalgic for the way music worked in the culture when I was younger. But as an economic enterprise, as a business, and as a thing where it’s like, well, artists put out albums, people buy albums and singles, and it’s played on the radio, we’re talking about a business model that got its start from a technology that’s not that old. The business model itself was basically just from the 1960s. We just were like, “This is how music works.” There was never any reason to think that was permanent.David: That is a great point. There was no reason to think it was permanent. To go back to Napster, I think piracy represented such a radical break from the previous paradigm, and there was a lot of hysteria and a lot of concern about it. Whereas to me, if you go back to the 1990s, the really big concern was that there was a thing called Universal Music Group that was brought to us by Seagram.Alex: Yeah, exactly.David: That was the bigger cultural problem of the late 1990s in the recording industry. Laura: Do you think that the focus on Spotify, and the focus right now on streaming as the villain of the music industry, has benefited all those other actors, because they’re so much more visible than Universal? You don’t hear people talking about the evils of the major labels in the way that you did when Prince was railing against his record label. David: Yes, I do think the focus on streaming companies obscures the fact that this was a system mostly set up by the major labels. And that is a system that they’ve been pretty fine with. I always think about it like this on the exec side. If you’re a record executive in the 1970s, you had to sell records. You really did care how many records Michael Jackson or Bruce Springsteen sold, because if they didn’t sell records, how could you make money? Versus in the 2020s, if you’re a record exec at the high level, you don’t do anything. You just know that you have market share. As long as I’m above 25 percent of market share, which is honestly impossible not to have when there are only three labels, you’re good. Laura: What do you think of artists’ efforts to try and change the current system? Is there any hope there? David: Over the last couple years, there have been a number of groups that have risen up to speak for artists in ways I think are really exciting. There’s been the Union of Musicians and Allied Workers, and a couple others I know throughout the country. I support that. But I do not particularly care for the campaign that are just yelling at Spotify in particular, because I do think it mystifies and confuses the issue when you just look at Spotify and don’t look at any of the major labels or any of the other folks. And then I think also because of that, folks don’t realize just how confusing the industry is. A small example of this is that if you go to Spotify and listen to something on Spotify radio, for an artist, the money generated from that on the publishing side—i.e. who wrote the actual song—that is regulated by the United States government, by the contract royalty board. They decide how much money those artists are going to get paid out from that, it isn’t negotiated between labels or anything. And that copyright royalty board is a three-member board that actually has a lot of control over a number of different digital streaming payouts. No one talks about them. And what happened over the last couple of years is that they tried to up how much they were going to charge streaming services, and all the streaming services fought it. Basically, they were like, “We refuse to pay out for this.” And what’s happened now, it’s been caught in this legal limbo. So I would love it if there are more artists’ outcries over things the U.S. government already has legal say over, rather than trying to appeal to the hearts and minds of private interests.Alex: It’s probably more effective to try to actually come up with a political solution than to just try to beg a private company to stop trying to take money for itself.Laura: So it’s better for artists if streaming services and labels have to negotiate with this huge entity called the U.S. government than with this little person who is making some music on private contracts. David: If hundreds of thousands of American artists were organized in a fashion to make demands of Spotify, I would love to see that. That would get stuff done very quickly. Hundreds of thousands of artists are not organized against Spotify. I’m going to suggest that we aim for that, but maybe try to figure out some other solutions along the way until we get there.

Read Morenzezmtqxmzatyzcyni00ntmyltk0n2etmmm2zdc0mmm4ywjinwy1ymi5nweymtaxzg

Month: May 2021

Entry #203 in the Dylan to English Dictionary, billed by author A.J. Weberman as “the most useful and authoritative translation of Bob Dylan’s poetry you can own,” provides the Dylanological definition of garbage as: “Empty talk, vacuousness, inferior work produced by other artists.” And Weberman, who lays claim to coining the word Dylanology, knows garbage. In the early 1970s, he was infamous for sifting through the trash cans outside Bob Dylan’s Greenwich Village apartment. Weberman was rummaging for clues, angling to unlock the mysteries of his idol: discarded song lyrics, intimate letters, something. What he mostly excavated, according to a 1971 Rolling Stone profile, amounted to “a mound of dog crap and a mountain of odoriferous, soiled disposable diapers.”Like many in the early 1970s, Weberman saw his hero as an apostate, who had forsaken his role as the voice of a generation. He engaged Dylan with open hostility, lurking outside his house and drawing him into a series of belligerent (and highly entertaining) phone calls. Weberman subjected Dylan’s lyrics to microscopic close readings and played his records backward to reveal hidden meanings. Weberman’s Dylan to English Dictionary is a similarly demented project: the result of ingesting every word of Dylan’s songs into an early computer using punch cards, to find a way into those famously impenetrable lyrics. The results may be wholly cockamamie. But the undertaking itself illuminates so much of Dylanology, a discipline animated by the shared belief that Dylan needs to be deciphered. The mission of the Dylanologist is to serve as codebreaker, or some augur of the divine.If Weberman was written off as an unhinged oddity in the ’70s, he’s an absolute pariah now. He has spent decades propagating phony theories that Dylan has AIDS (contracted from a dirty heroin needle) and, more recently, that Bob Dylan has died, a casualty of the coronavirus pandemic. Yet the discipline he invented lives on and is now serious business. There’s no mention of the disgraced dean of Dylanology in The Double Life of Bob Dylan: A Restless, Hungry Feeling (1941–1966), the first volume of a new biography by Clinton Heylin, whose own body of Dylanological research numbers eight books, including the thrice-revised biography Behind the Shades and a multipart analysis of each of Dylan’s 600-plus songs. Weberman’s Dylanological preeminence can, by now, be safely disavowed.Certainly, Heylin sets out to elbow past all other comers, making bullying attempts to clear the crowded field of Dylan researchers, biographers, and armchair obsessives. Ian Bell’s Dylan biographies are “pseudo-historical.” An introduction to a book of Dylan photographs written by august rock journalist Dave Marsh is “insipid.” Longtime confidant Victor Mayamudes’s Another Side of Bob Dylan is “thin gruel.” The online resource About Bob Dylan proves only “ostensibly reliable.” Dylan’s own 2004 memoir, Chronicles: Volume One, is “unreliable,” something that even rookie readers took for granted at the time of publication. Readers are meant to be humbled before such pomposities. Here comes Clinton Heylin to hew a path through the trash heap of vacuous biographies and inferior works. Something is happening here, and this guy—and only this guy—knows what it is.Heylin’s book arrives at an opportune time. Bob Dylan turned 80 this week. Last year’s Rough and Rowdy Ways album received the sort of universal critical acclaim that has eluded Dylan in recent decades: a welcome (and frankly relieving) reminder that his genius could still find purchase as he entered his ninth decade. He also made headlines for striking a blockbuster deal with Universal Music, which purchased Dylan’s robust back catalog for an undisclosed sum (rumored at about $300 million). Between such big-ticket accounting, and the recent work’s mournful, in places downright funereal tone, it’s hard not to be reminded that Bob Dylan will not be here much longer and is, as they say, “making arrangements.”There’s also the matter of Dylan’s personal archives—a massive data dump of notebooks, contracts, manuscripts, films, tapes, and correspondence—being sold off to the University of Tulsa in 2017. Heylin’s new research draws heavily from this collection. More than a conventional, or conventionally readable, biography, A Restless, Hungry Feeling feels more like a hefty appendix to extant Dylan bios, or an advanced research seminar in Dylanology. Heylin lays out his own project a little ghoulishly, declaring it “a new kind of biography written in the same milieu as its subject but with the kind of access to the working process usually possible only after an artist’s death.” In his music and presentation of himself, Dylan has always been mercurial, recalcitrant, unknowable: a wiggly mess of creative impulses that Heylin hopes to pin down, playing the Dylanologist as lepidopterist. At the risk of dismissing the whole venture out of hand, I can’t help but wonder how useful this is. First of all, there’s a simple matter of credibility. Heylin, like anyone who cares even a little bit about Bob Dylan, takes for granted that his subject is a master fabulist, if not a compulsive liar. From his made-up name to his imagined backstory, to his preternatural ability to mimic folk and blues forms that Heylin describes as “uncanny,” the “real” Dylan has always seemed like a bit of a phantasm. This idea, of Dylan telling truths from behind a mask, is productively mined in his 2019 collaboration with director Martin Scorsese, The Rolling Thunder Revue—an entertaining conflagration of tour doc and playful fabrication that Heylin waves away as mere “mockumentary.” If this penchant for fabulism is so deeply baked into Dylan’s DNA, then why should anyone reasonably expect that his private manuscripts or personal letters would adhere any more to the capital-t Truth?Dispelling Dylan’s various myths, self-styled and otherwise, also has a diminishing effect. It’s like explaining a magic trick. Throughout his career, Dylan’s identity mutated—from warbling folkie to motor-mouthed rock poet to country troubadour, Christian evangelist, and beyond—as he followed his muse, or his whims, or whatever. He defies expectation and seems creatively beholden to not much beyond his own shifting fancies. I imagine this is why most people like Bob Dylan. Because this is why I like him. And if other people like him for other reasons? Well, then that only certifies his status as the man of manifold possibilities, a Bob for all seasons. Rifling through old letters and contracts for clues to the “real” Dylan can feel a little beside the point, like fact-checking The Iliad against archaeological excavations from ancient Greece. Does Heylin expect to find some smoking gun, a scrawl in an old journal reading, “I am going to make a point of performing my identity, to vex and frustrate the public, and particular critics and biographers?” Such a po-faced confessional seems unlikely, and Heylin knows it. Even the titular “double life” conceit of these new biographies seems insufficient for an artist who recently boasted of containing multitudes.Heylin’s book is riven with the sort of nastiness that marks first-rate obsessives, whose interest in a subject calcifies in time into a thinly veiled hatred.Heylin’s book betrays the frustration of this knowledge. It’s riven with the sort of nastiness that marks first-rate obsessives, whose interest in a subject calcifies in time into a thinly veiled hatred, as the object of their affection fails to reveal its fullness. (A few years back, I was amused by a conspiracy maintaining that The Beatles did not, in fact, exist at all. For such true fanatics, obliteration becomes a form of ownership.) The feeling that Heylin is spoiling his subject is compounded by the author’s writing, which has its own curdling effect. It’s not long before Heylin’s parenthetical corrections of quotes and typos, and his excessive deployment of “[sic]” seem like little more than rank pedantry. His persistent use of locutions such as “learnt” and “’twas” and “knew not” is grating in its pretension. Ditto his reference to a 2011 auction block of Dylan manuscripts as “mouth-watering fare.” Never missing an attempt to diss Dylan’s half-remembered, half-imagined memoir, Heylin repeatedly refers to Dylan as “the Chronicler.” Not since a 2013 Metallica biography habitually identified drummer Lars Ulrich as “the Young Dane” do I recall being so twitchily irritated by a cutesy diminutive.A pervading sense of mean-spiritedness is never far from these pages. That tone is most obvious in the author’s chary regard of his icon. There is persistent air of suspicion, as Heylin develops the image of Bob Dylan as a “Mr. Hyde, a boozer and pill-popper and womanizer,” who would alienate friends and loved ones as he sculpted the popular persona of an “alter-Dylan.” Yet how suspect is this turn, really? As Dylan moved from folk darling to proto–rock star—realizing, per Heylin’s anguished verbiage, that “his preordained role was to tie a lover’s knot around the red, red rose of folk-rock and rock ’n’ roll’s thorny briar”—he became “public property.” If a Pynchonian abstention from public life was, by 1965, pretty much impossible, then Dylan did the next best thing. He recast himself as an obstinate enigma, quarreling with nosy journalists (merely “frustrated novelists” in his estimation), foiling folknik audiences with his played-way-too-loud rock music, and trolling The Beatles. (Heylin recounts the first encounter between the two most important pop acts of the 1960s in hilarious detail, describing Dylan answering the phone in the Fab Four’s NYC hotel suite with “This Is Beatlemania here.” Whether such antics are snide or hysterical likely boils down to personal taste.) If Weberman’s Dylanophilia was openly combative, Heylin’s has soured into sniping and cattiness. He writes about Dylan like a posturing pickup artist negging for attention.Still, Heylin’s claim to be king of Dylanologists may well be apt. If nothing else, A Restless, Hungry Feeling serves as the literary equivalent of being stuck at the bar next to a Dylan Guy: the sort of superfan who bores with tedious trivia and is all too eager to correct any half-formed opinion offered by the more casual listener.Heylin’s subsequent volumes, and their marshaling of the Tulsa archives, may prove more fruitful, if only for rounding out the history of periods in Dylan’s career that aren’t so exhaustively diarized. However revisionist its approach, A Restless Hungry Feeling can’t help but slog across land well trodden. Even casual fans are likely familiar with the highlight reel of Dylan’s mid-’60s apostasy: going electric at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, being decried as a “Judas” during a 1966 concert in Manchester, etc. Let’s see lengthy fact-checks on the story of Dylan performing all of Blood on the Tracks solo for Graham Nash. Or six pages on the time he played a harmonica in the wrong key on Letterman. Where’s the tell-all of Dylan’s little-seen 1987 film Hearts On Fire, directed by the guy who made Return of the Jedi? Dylan’s mid-’60s run has already merited intense focus. Scorsese’s 2005 doc, No Direction Home, which runs three and a half hours, also wraps in 1966. Greil Marcus, likewise, has dedicated an entire book to 1965’s “Like a Rolling Stone.” This investment makes sense. Dylan’s shape-shifting in this period spoke not only to the fluctuations of popular music taste but the whole world. The so-called youth culture was aging out of blue jeans and bubblegum and making new demands of the world. Dylan once said of Woody Guthrie, “You could listen to his songs, and actually learn how to live.” For the generation following in the heels of the beats and the folkies, Dylan’s music proved similarly life-affirming.A Restless, Hungry Feeling ends teasing Dylan’s fateful motorcycle wreck in the summer of 1966, “when he went for a spin on his cherished Triumph, and nearly met his Maker.” It’s a common fork in the understanding of Dylan’s career. It marked the end of a period of rabid productivity that birthed Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited, and Blonde on Blonde—a remarkable trifecta of records that stand as the apogee of Dylan’s trademark impenetrability, lyrically and otherwise. Some claim the crash also changed Dylan’s vocal timbre, or even that it snuffed out some divine spark of inspiration flickering within him that would never burn as brightly again. It also marked Dylan’s withdrawal from society. It would be eight years before he would tour again, during which time he cultivated what The New York Times termed the “jealous protectiveness of his privacy” and “the legend of a mysterious recluse.” Like another New York City transplant of the era, Andy Warhol, Dylan was preternaturally hip to the idea that an artist’s real art was himself. Heylin’s book speaks to how attentive Dylan has always been to this legend. Raised on rock ’n’ roll, he was a product of celebrity culture and ambassador of the emerging form of popular music. With an intuitive understanding of stardom and its wages, he defined the times by keeping half a step ahead of them. Like another New York City transplant of the era, Andy Warhol, Dylan was preternaturally hip to the idea that an artist’s real art was himself. Beyond his forbidding talent as a songwriter and composer, Dylan was smart. And savvy. And funny. And always desperate, as he told the Toronto Star’s Robert Fulford in 1965, “to get rid of some of the boredom.”Dylan’s music, at least in the uberproductive interval described in Heylin’s new volume, spoke in a way that was universal and nonspecific. It’s as generous as it is impregnable in affirming different lives in different ways. If Heylin or any other biographer finds something sneaky or duplicitous, or underhanded, or otherwise Mr. Hyde-like about this, it may speak more to their character than it does to Dylan’s. Because, as Dylan once snarled in a testy telephone exchange with A.J. Weberman, the greaseball granddaddy of Dylanology and still the artist’s only worthy nemesis, “I’m not Dylan. You’re Dylan.” The rest, Dylanologically speaking, is garbage.

Read Morenzezmtqxmzatyzcyni00ntmyltk0n2etmmm2zdc0mmm4ywjinwy1ymi5nweymtaxzg

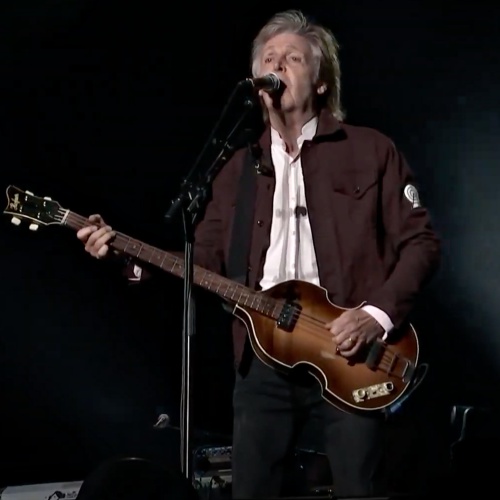

The enduring musical power of The Beatles helps carry Sir Paul McCartney to the top of the Music Rich List, according to

Read Morenzezmtqxmzatyzcyni00ntmyltk0n2etmmm2zdc0mmm4ywjinwy1ymi5nweymtaxzg

Foundations: Babe Rainbow

Digging into their psychedelic bedrock…Babe Rainbow are part of a new wave of lysergic wanderers who are establishing Australia’s reputation as a psychedelic citadel.

Yet theirs is a universe seldom explored. Fuelled by endless daydreams, friendship, and long hours surfing, the band’s approach grapples with a hedonistic form of freedom.

Take new album ‘Changing Colours’. A warped alt-pop template that feels as though it’s been distorted by ferocious sunshine, the song cycle moves from all out guitar frenzy to an actual, bona fide Jaden Smith collaboration.

A wild ride, it could well be the finest thing Babe Rainbow have yet put their name against – which, given the strength of their catalogue, is a strong compliment.

– – –

‘Surfers Mood Vol. 3’ (The Bob Simmons Memorial Album) (As picked by Angus, vox)

This is an important moment because the Bob Simmons album took me out from Grade 11 Physics and Earth Sciences all the way to out the back at Fingal Point on a shimmering wing. It was the backing track to our original explorations in anti-hero counter culture at our buddy Isaac’s parents farm in Upper Duroby near Tumbulgum and the original bookshop score in Murwillumbah where old Bruce taught us how to paint and Jack got us all started in playing music ourselves.

Surfing is a clean connection to the Earth and something that probably brought us all together more than anything. The songs are all just full moods and the singing sections are deeply enchanting I reckon this and the JJ. Handkerchief NZ / H.O. Nimrod stuff all deserves a little kiss for keeping us in line while we were still deciding what direction we were off in.

We still surf together every day and I play this record religiously at our dinner parties with all the wives and babies. One of the most exiting things I can imagine is sharing the magic of peaches and surfing with our children in a couple years when they can dig it legit at midnight on Pier 13… see you at Malibu!

– – –

Sun Ra and His Arkestra – ‘The Antique Blacks’ (As picked by Miles, drums)

Sun Ra’s output, whether it be music, poetry, performance or a political idea / discussion, questioned, dismantled, and shed new light on boundaries in music and the world they were surrounded by.

Sun Ra often mobilised ideas and energies of people from a surrounding political climate, in combination with a deep knowledge of history and religion which spanned all continents and cultures, as well as Sun Ra’s own thoughts and understandings, to offer truths and new light to an audience who may have lacked access to such knowledge and information or felt politically aligned. Often showing the imperial lens and Euro-centric way of viewing the world to be false and damaging in a way and using their music as a safe and nourishing space for an audience to experience the world of truths, where they are accepted and welcome and celebrated.

This record, for me, sums up a lot of sounds Sun Ra and band explored. Songs such as ‘Song No. 1’ and ‘Space Is The Place’ offer a strong groove and linear percussive backing to elevate and audience to a place of joy, these songs are arguably more accessible to a modern audience.

This album contains also many tracks that highlight the group’s interest in electronics and what some would call ‘noise’ music or ‘free jazz’, music that I feel is of great importance and deeply interested in.

– – –

Herbie Hancock – ‘Head Hunters’ (As picked by Elliot, bass)

This 70s album bought the high flying birds down from the sky. The head hunters were back on earth. Forging out of the ground the molten of jazz and blues. When I heard this album everything after seemed easier. My mind and spine realigned.

When the groove is in the bag you are cruising. And this album has riches and treasures that will supply the necessities for centuries of reinventions. For bass players devoted to the groove you will find in this album the holy groove of ancient ecstasy. For party people you will find the songs that keep the spirit awake all night.

And for anyone who hasn’t heard this album yet be prepared to feel the rush of lusty vibes we come to think of when we think of the sexy 70s.

– – –

The Incredible String Band – ‘5000 Spirits or Layers Of The Onion’ (As picked by Jack, guitar)

Robin and Mike are a beautiful inspiration. Their poems, and the melodies and music they use to deliver them, are magic.

This – their second album – was them transitioning from traditional folk to psychedelic folk and got me pretty good in the depths of my psyche. Encouraging awe of the natural world, playfulness and whimsy amongst very good instrumentation. Utterly beautiful love songs to cool blues ditties and thought provoking long-winding stuff.

From what I’ve read and YouTube’d they seemed like musicians-musicians in the late 60s scene. Not at all pop-oriented but probably managing to describe, through their music, where everyone’s imagination wanted to go.

– – –

The Zombies – ‘Odessey And Oracle’ (As picked by Wayne Connolly, producer)

With the CD re-issue trend in the mid-‘90s, records from the past started appearing as if they’d been buried in a time capsule. ‘Odessey and Oracle was hailed as one of the great lost albums and it was. Every luminous track is as brilliant as the last.

There were lots of discussions about it with artists I was recording at the time – you can hear its influence on You Am I’s ‘Hourly Daily’ with the addition of mellotrons and strings. Elsewhere, Elliott Smith covered ‘Care of Cell 44’, and you’d have to imagine artists like The Shins were taking a little inspiration from it, too.

In an era when pummelling a drop-tuned guitar was still pretty on point, ‘Odessey And Oracle’ was refreshingly full of rich melodies, wondrous vocals and harmonies, and complex chord structures.

The cover design suggests psychedelia, but it’s really gorgeous orchestral pop, recorded at Abbey Road in the weeks after the Beatles finished ‘Sgt Pepper’. The Zombies broke up before it was released and despite an international hit with ‘Time Of The Season’, it never really received ‘classic album’ status until its reissue in the ‘90s.

‘This Will Be Our Year’ and ‘Friends Of Mine’ are standouts but ‘Maybe After He’s Gone’ is the high water mark for sunny baroque pop with a deeply sad lyric.

– – –

Babe Rainbow’s new album ‘Changing Colours’ is out now.

Photo Credit: Marclay Heriot

– – –

Join us on the ad-free creative social network Vero, as we get under the skin of global cultural happenings. Follow Clash Magazine as we skip merrily between clubs, concerts, interviews and photo shoots.

Get backstage sneak peeks, exclusive content and access to Clash Live events and a true view into our world as the fun and games unfold.

Buy Clash Magazine

Read Morenzezmtqxmzatyzcyni00ntmyltk0n2etmmm2zdc0mmm4ywjinwy1ymi5nweymtaxzg

On this episode of “Everything Fab Four,” Nancy Wilson of Heart talks glass ceilings, guitars, rock and the Beatles

Read Morenzezmtqxmzatyzcyni00ntmyltk0n2etmmm2zdc0mmm4ywjinwy1ymi5nweymtaxzg

Is there ‘LIFE ON MARS’? Exploring his new EP…One of the greatest challenges an electronic producer faces is adding the aspect of emotion to their music. With technology so advanced, the genre can come across as too clean, lacking that relevant rawness for people to connect with. However, in the case of Bobby Nourmand’s latest EP ‘LIFE ON MARS’, we see an artist go totally against this notion. Inspired by the life changing birth of his first child, we see the release act as a sonic journey, starting with the sense of fear-fuelled isolation, and ending with the feel of release and freedom. With glimpses of ambient, left-field and futurism throughout, we see an artist in Bobby at his most refined, pushing the boundaries of what electronic music can deliver.

Bobby started his career in the conventional manner of DJing at clubs throughout New York. Surrounded by talented artists, his eyes were opened to the endless possibilities a producer has at their hands. It was that moment he went into the studio and never looked back. “At the age of 23, I got sober and started to pursue my craft into a career. Totally fuelled by passion and to spread the love of music.” He explains: “This journey started in ChinaTown at a venue called Apotheke where I got my first residency. These nights were magical and on fire, literally. Specifically playing other people’s music wasn’t enough. I wanted to be able to express my own message and connect to the audience on a more personal level whether in person or in the privacy of their own experiences, it sparked the flame to create my own music.”

Finding his sound by remixing iconic tracks from the likes of The Doors, The Rolling Stones, The Beatles and Billy idol, Bobby found himself looking at an alternative dance sound from the very start. That was what paved the way for his career, as the artist explains: “Maintaining the integrity of these classic tracks, the production was minimal. These releases were seen and heard by millions of listeners which gained the attention of the A&R’s at influential labels.

This led to the demand for my own productions because, nobody would’ve been able to clear the samples I was using. ‘SMOKIN JOE’ was my first original release, taking my career to new heights.”

Now, with the release of ‘LIFE ON MARS’ we see the artist move in a new direction. Fuelled by the life changing moment of becoming a father, the EP represents a turning block in both his personal life and artistic career. “LIFE ON MARS was the result of a need to connect deeper into myself, without the influence of my surroundings. This process took over two years to complete from start to finish.” He proclaims, “The journey began with lighting SAGE and getting lost in a Juno-60. There was no shortage of inspiration, as I was filled with strong emotion and the ability to communicate my subconscious through the machines. They came to life. Most of these takes were done on analogue gear which lasted from seven to 30 minutes of granular synth work, my heart bled into and through the speakers.”

As listeners, I think we can often forget that artists are humans too. Riding the same highs, and suffering from the same lows, we all bleed the same. Although, this experience has served like no other to Bobby, a total rebirth in many ways, with endless lessons already been learnt. “Time is much more valuable. Each moment spent creating is with intention, focus and gratitude. There is no way to articulate the experience of holding your child for the first time.” The artist states, “It was an outer body experience. Once skin to skin contact was made, green light filled my body starting with my heart, into my body and then the entire room was radiating with her aura. This healing process inspired the release of LIFE ON MARS. There was a switch once I held her and became a father.”

This story is told sonically throughout. With the EP starting with the minimal, ambient ‘SAGE’ – taking name from his daughter – moving towards left-field with ‘VISIONS’ and ending with the forward thinking ‘SANTO’. Each song on the EP transmits a certain mood, taking the listener on a journey through the artists life. It was an experience that came totally natural to Bobby, often crediting it to his subconscious, rather than forcing anything at all. “My body was just a channel of the source fuelling the inspiration. By allowing this larger energy takeover I was just a witness to what was being created. The less I got in the way, the better it sounded.” He explains, “Inside out rather than outside in. The project started out from total humility, stripped down to the core. It all took form on its own. Genres are helpful once things are complete and ready to be packaged for our listeners and peers. But how can you package something which has not been made yet, that would be suffocation.”

What strikes me about the release is the freedom of Bobby’s approach. Without any form of sonic inspiration, everything that ensued was a culmination of sounds that he holds close to him. He explains this process by saying: “Each song served to purge and turn myself inside out in order to offer this being the most pure experience. The absence of my ego and all else which could get in the way of being the best version of myself. The shift happened throughout the artistry, starting off stripped down to just a heartbeat then journeying through the darkness and towards the light and eventually freedom and clarity.” Some lyrical inspiration came from the likes of the Beatles and Kurt Cobain, perhaps seemingly odd sources giving the futuristic sounds on the EP, but these arrived naturally and helped to pass on heart felt messages.

With a release as personal as this one, that contains as much heartfelt emotion, there’s sure to be a message to all those listening. For Bobby, that message is one of hope. Prior to this experience, he found himself in a dark place, void of any faith and feeling lost, contemplating the meaning of life, and then he found himself blessed. “The smallest sliver of light can radiate in the darkest times. LIFE ON MARS is that light – a journey that was born out of an awakening.” Bobby proclaims. “Its mission is to clear the air through deep connection – a soul search. You are not alone. No matter what it is you are going through at this moment, there is light at the end of the tunnel.. Without darkness there is no light. Embrace the journey and dive in.”

‘LIFE ON MARS’ is released to the world via Bobby’s own label ‘Deep In The Night’. Created in 2018, the label has since become his home, as explains: “The label came to life in order to showcase some deeper, darker and harder hitting tracks, but genres are dead-end descriptions. My vision is to have the label tell a story, rather than evoke one-off, singular, specific emotions. The music won’t stick to trends, instead highlight the persona of each artist. Moving forward, the label will not only showcase the dark but also the light.” The EP also features the single ‘VISIONS’, which was released via Moscoman’s Disco Halal label in August 2020, becoming one of the first names to feature on the labels ‘Singles Club’. With the song’s alternative nature, it felt like a perfect match, as Bobby describes: “It is an honor to be a part of Moscoman’s Disco Halal family. Once he heard the track and gave it a green light it just felt like the right home for it.”

A release like ‘LIFE ON MARS’ really does show the impact real life has on artists. Made over the course of two years, you can hear just how life changes for Bobby throughout. It’s personal and introspective and it really pushes the agenda of what electronic music can be. A new chapter is being written in the artists life, and one we’re sure to eagerly wait to see what comes next, as Bobby ends by saying: “This release has led to a newfound freedom and the ability to communicate emotions more intimately. LIFE ON MARS has been a therapeutic journey which will forever stay with me as a unique being and also as an artist.”

– – –

– – –

Words: Jake Wright

– – –

Join us on the ad-free creative social network Vero, as we get under the skin of global cultural happenings. Follow Clash Magazine as we skip merrily between clubs, concerts, interviews and photo shoots.

Get backstage sneak peeks, exclusive content and access to Clash Live events and a true view into our world as the fun and games unfold.

Buy Clash Magazine

Read Morenzezmtqxmzatyzcyni00ntmyltk0n2etmmm2zdc0mmm4ywjinwy1ymi5nweymtaxzg

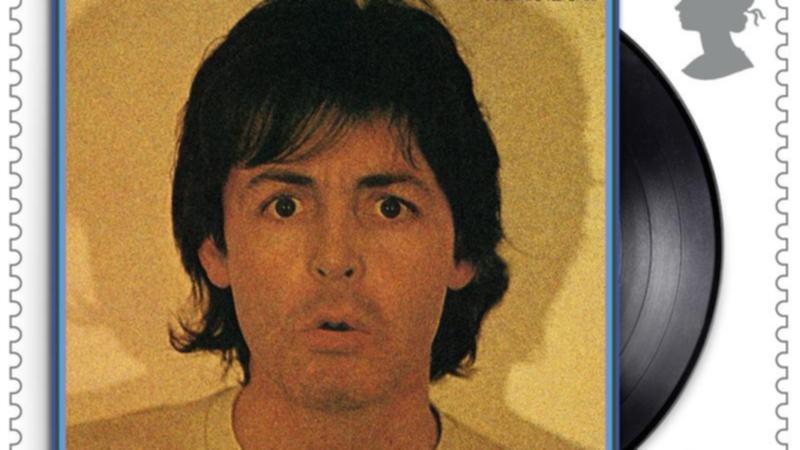

Paul McCartney celebrated in stamps

Former Beatle Paul McCartney can now add a personalised set of stamps to his long list of accolades.

Read Morenzezmtqxmzatyzcyni00ntmyltk0n2etmmm2zdc0mmm4ywjinwy1ymi5nweymtaxzg

In Conversation: Stephen Fretwell

How fatherhood and Speedy Wunderground’s Dan Carey fuelled his new album…Stephen Fretwell’s songs have a magic touch.

And as the songwriter returns to the public eye, following a thirteen year hiatus, he can feel safe in the knowledge that his magnificent, haunting new studio album ‘Busy Guy’ is complete, set for a glorious summer release.

Growing up in Scunthorpe, the musician and songwriter, who is now 39, moved to Manchester in the early nineties. Living and breathing music in and around the Northern Quarter, his choice of city showed his desire to establish himself as an artist, while engaging with the tremendously influential music culture.

Featuring songs like ‘Emily’ and ‘New York’, Fretwell’s debut album ‘Magpie’ came out in 2004, followed by ‘Man On The Roof’ in 2007. As much as performing alongside bands such as Oasis, Elbow, Keane, and playing bass with The Last Shadow Puppets, his song ‘Run’ was part of BBC1’s sitcom Gavin and Stacey, where it became an instant classic.

Considering the commitment to caring for his two sons, and not feeling his career was taking the direction he wanted, he took the decision to step away from music, and focus on family.

Encouraging, gently pushing him to release, regular conversations with close friend, producer Dan Carey, of Speedy Wunderground, helped to build confidence in the songs he was writing.

– – –

– – –

What’s it like to return and have made a record after thirteen years?

There’s a positivity. It’s enjoyable to think that I’ve done something that people are interested in, it’s like a muscle memory permeates in the brain. It seems novel, and I can enjoy it without feeling too self-conscious. When I was young I used to ‘die’ of embarrassment, in an interview I’d just be completely monosyllabic, I didn’t wanna give the game away, I was just a geek musically. But now, I don’t want to hide any elation that people like these songs, it’s lovely.

Would you say an event prompted your comeback, or was it a gradual process?

My natural stage is someone who wants to make things, I think maybe I should write a novel, get some canvasses and do some painting or write a song. When my children were born that overtook the mentality of I should be creative, I should do something, and I focused everything on them. When they got to school age and didn’t need as much focus I started to think about what to do.

The music industry you return to is different to than the one you left, do you see that too?

I don’t really see it, I look at the whole thing very fondly and uncritically, with a sense of awe compared to when I first got into it as a young kid, when you’re careful, you don’t know left from right. I look at music, everything creative these days as just positive, the world that we live in it seems that I think there’s going to lots of amazing things that are going to come out of this period that we’ve been locked. I hope people have been forced to look at themselves and assess themselves in close quarters and create things.

Dan Carey plays a key part in your music journey, tell me about the relationship.

Dan’s someone, who has challenged me and questioned what it is that I do, what the point of writing music is. That’s the constant point of conversation I’ll have with him, of him questioning whether something is needed, whether it’s worthwhile, if it needs to be re-thought, and that’s difficult to go up against, sometimes. Honestly, he’s probably the most important person creatively that I ever came across in my life.

How did you and Dan shape the conversations around this album?

For ten years we talked about what a record would sound like, in a casual way, we’re close friends, he was supportive without being controlling. I didn’t really know how to make a record or what to do, I kept making recordings, setting the microphone up, recording songs and sending them to Dan. We would talk about it. Then one day, around mid-May, I set a microphone up in the room, and I recorded what I thought was the album from start to finish.

I sent it to Dan, and he called the next morning. He said, this is it, we need to make the record now, and I phoned Soho Studios. This record is authentically written, it’s a true record in the subject, but also the craft that went into it, Dan encouraged me to focus on the art of songwriting, he said, I’m someone who can do this. I didn’t really believe I was, I thought I was a pretend Ryan Adams, I thought I was a phoney.

‘Busy Guy’ belongs to a certain type of record that doesn’t get made anymore. Being encouraged, did your sense of freedom grow?

That is true, I wouldn’t dare to have made a record like that if it wasn’t for my manager Ian McAndrew and Dan Carey both telling me that it’s ok. I’d have thought, I’m going to business with all these people, I need to make Radio 2 A-list singles, it felt as if it would have been rude to stand up and say I’m going to make this acoustic record, but my manager and Dan protected it and steered me away from doing anything that wasn’t authentic, so I feel very privileged.

– – –

– – –

That comes across in the song ‘Almond’, how was the writing process?

I wanted to create something that moulded in with themes across the songs, there’s a lot of birds and coastal activity. That song took me the longest. I gave up smoking when my first son was born, and I left London. It started out as a love song to London and cigarettes, because they were the two things I really missed, but I ended up back in London, and I started smoking again. It almost became a project that ran beside the other songs.

Every morning when I started digging into one of the songs, when I got stuck I’d go to ‘Almond’. I was trying to talk about the relationship I had with my wife, we were friends, we met at university, she was a philosopher, I was studying English, I moved on to something else and later dropped out. But she became a really good friend, the song is an attempt to take in different scenes of that relationship.

The album tackles the breakdown of your marriage, how did you know things had taken a bad turn?

My wife started to say she wasn’t happy about things and asked me to give her some space, and that’s when I started focusing on the record. We’re still very good friends, we have our two sons, they are nine and six. In lot of ways I fucked my marriage up because I wasn’t working, and I ended up washing pots in a JD Wetherspoons on West Street in Brighton, it wasn’t the most attractive look after being an international songwriter, which I was before I was a pot washer. That’s why I wanted to go to university, I thought, I can’t live the rest of my days being one of these musicians that sit in pubs talking about supporting Dodgy in 1996.

How much do your sons know about your music background?

My music career and my sons is a funny situation, because I never said anything about it for years. We moved to Brighton when my younger son was two years old, and everyone there’s a musician. When he was seven he said “dad, I’ve just seen you on someone’s phone playing on a stage with a guitar.” I asked him what he thought, he said “I can’t believe it’s what you do”, I said, it’s what I used to do. Then he walked into the front room, turned back and said “you never told me about Gavin and Stacey!”

Describe when you took a step back from music. What initiated it or was it gradual?

I didn’t feel that the music I was making was right, I got dropped by my label. Is there any point if you‘ve not got anything to say, if you don’t feel compelled to create something and believe in it. Because I’d never made that much money out of music, I was never a very lucrative artist, I couldn’t just flex the muscle and go on tour, I would have done that because I had responsibilities for my children. When they were born, it seemed as though music meant having to give so much to something that probably wouldn’t be lucrative, I wouldn’t be with my sons, it didn’t seem to make any sense to say ‘I’m a poet, I’m an artist, and this matters more.’

You played alongside Oasis, Keane and Elbow, and John Squire.

Yes, one of the first gigs I ever did was supporting John Squire, when he came back after The Stone Roses. If you can imagine the crowd, walking into a Stone Roses crowd with an acoustic guitar, everyone’s just throwing plastic cups, shouting about wanting The Roses. But I was always a music fan, when I wasn’t playing I was just wanting to talk to people about music, I think that’s what made people ask me to come on tour.

– – –

– – –

Were you proud when Arctic Monkeys covered your song?

Yes, that was a big turning point in my life, because I know Alex Turner – he has the same manager. I met him and Miles Kane in New York, and I ended up playing bass with them, so I knew them from The Last Shadow Puppets. But when he covered that song, it was a big deal, it really did spur me on to take it seriously.

What do you feel you gained from playing with TLSP?

Oh man, that was unbelievable, it was like hanging out with The fucking Beatles. I remember going to Paris, and people were chasing them down the street, it was hilarious and quite overwhelming, the kind of gigs I’d normally do, there was no distance between the fans and you, when you walked off stage, you went straight into a room, if someone wanted to come in, they just did. It was fantastic to work with Alex, I think he’s one of the finest songwriters.

You were living in Manchester at one point. It’s a terrific city, what was your reason for selecting it?

I didn’t do very well in my A-Levels in college, because I have ADHD, I messed my coursework up. I was put forward to go to a top university to read English, but I didn’t go to any exams, I had an E in English language and a D in English literature. All my friends were going to Manchester University, I called Salford University and asked if they would take me based on these grades, I explained I had had a bad time, the admissions tutor let me in. I just wanted to be with my friends and get out of Scunthorpe, I thought, I’ll get to Manchester, and I’ll somehow make it as a musician.

How well did you know Guy Garvey? How did the relationship develop?

I bumped into Guy Garvey at an acoustic night, I didn’t know, who he was. I played a couple of songs there, and Garvey and Craig Potter came up and said they really liked my music, would I consider coming to Liverpool and record some songs? I just stood there looking at these two weird guys trying to make me go to Liverpool with them, and I ran out of the place. About three weeks later a mate called to ask if I’d heard of Elbow? I started playing their record every day.

I had moved to a flat on Oldham Street, across from Night & Day Café, I thought this is where it happens, this is where I’ll be able to make it. One day I saw a guy walking down the street, I went over and asked if he was in Elbow. I told him, I liked the album, and he just said “all right, cool”. I couldn’t work out why he was being off with me, he said I’d been rude the other day when they asked me to come and record songs, and then he walked off. I couldn’t believe it was him, I spent about five weeks trying to explain the situation.

But he eventually came around. How immersed were you in Manchester’s music culture?

Garvey became the biggest supporter of my music throughout Manchester, inviting me to support them at Shepherd’s Bush Empire, that was a big deal. When you come back to Manchester after doing something like that, everyone’s talking about it. I met I am Kloot, Alfie and the Twisted Nerve label. I met Badly Drawn Boy – Damon Gough – he’s one of my best friends. I got into that world and became part of it, it was amazing. The place’s focused on creativity. There’s a Mark Radcliffe quote about how people in Manchester think a table is primarily for dancing on, there’s not a truer quote about that place, it’s focused on energy of enjoying yourself in a wholesome way.

How do you see your music career evolving?

I’d like to make another record. Left to my own devices, I’m always trying to create stuff, but whether that’s any good, and anyone wants to know about it, is another thing. I hope that I can keep making things, but I’m not necessarily someone, who thinks those things should be shared, it’s a truth that I’ve learnt about myself that I’m job dodger, constantly trying to dodge, trying to get a proper job, that’s the best way to describe it.

– – –

– – –

Stephen Fretwell will release new album ‘Busy Guy’ on July 16th.

Words: Susan Hansen

Photo Credit: Holly Whitaker

– – –

Join us on the ad-free creative social network Vero, as we get under the skin of global cultural happenings. Follow Clash Magazine as we skip merrily between clubs, concerts, interviews and photo shoots.

Get backstage sneak peeks, exclusive content and access to Clash Live events and a true view into our world as the fun and games unfold.

Buy Clash Magazine

Read Morenzezmtqxmzatyzcyni00ntmyltk0n2etmmm2zdc0mmm4ywjinwy1ymi5nweymtaxzg

Live music returned to the birthplace of The Beatles after a long coronavirus-enforced silence on Sunday when the English city of Liverpool hosted a one-off music festival to test whether such events spread the virus.

Read Morenzezmtqxmzatyzcyni00ntmyltk0n2etmmm2zdc0mmm4ywjinwy1ymi5nweymtaxzg

“I just think it worked perfectly with the band and the song and John being John. I loved that moment,” drummer says of his favorite Beatles track

Read Morenzezmtqxmzatyzcyni00ntmyltk0n2etmmm2zdc0mmm4ywjinwy1ymi5nweymtaxzg